Earliest Versions of the Legend

The earliest versions of the King Arthur legend bore only a few similarities to the modern story as it has come to be known. The earliest versions didn't refer to Arthur as a king at all, but rather, as a great war commander who led several battles defending Britain from invaders after Rome withdrew in the fifth century. The main invaders who plagued Britain during this time were tribes of barbarians known as Saxons, Angles, and Picts. These tribes are featured prominently among the earliest references to Arthur.

The earliest legends referred to a hero known as Arthur, Artur, Arturo, Artos, and various similar names. The legends tell that throughout his life, he had two (later, three) wives who were all named Gwenhwyfar (who later became Guinevere). Both Arthur and a warrior named Medraut (later, Mordred) were killed at the Battle of Camlann, although the earliest legends do not mention whether Arthur and Medraut fought each other, or if they were even enemies.

The earliest tales of Arthur were spread largely by word of mouth, and very few written accounts survive. Of the ones that do, we do not have the original documents, only copies which were made centuries later. Historians are not only unsure of when these copies were made, but also whether or not the copyists added certain tales of Arthur to the originals. As a result, it is not possible to determine which version of the legend is the oldest, as we cannot even be certain of the dating of the documents that we do have.

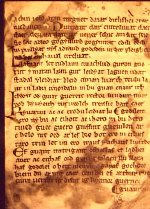

Page from a 13th century manuscript of Y Gododdin, the earliest

known text to mention Arthur.

Page from a 13th century manuscript of Y Gododdin, the earliest

known text to mention Arthur.

If we assume that the standard, accepted dating for each document we have is accurate, and that

medieval copyists did not alter them at all, then the earliest text we know of which mentions

Arthur is the Welsh poem Y Gododdin. Y Gododdin is not a tale about Arthur,

but rather, a poem dedicated to the men who died in a battle defending Britain from Angles.

Y Gododdin only mentions Arthur in passing, when it praises a warrior who

slew 300 enemies on the battlefield, adding that in spite of his prowess, he was not Arthur.

Another early reference to Arthur appears in the Historia Brittonum ("The History of the Britons"), which is usually attributed to the ninth–century monk Nennius. The Historia Brittonum details twelve battles that Arthur fought, and says that he carried the image of the Virgin Mary on his shoulders during one battle, and singlehandedly slew 960 men during another. As one can see, if there was indeed a real Arthur, even the earliest surviving accounts of him seem to have been written long after the facts were distorted and he had passed into the realm of mythology.

As tales of Arthur were told and retold, they seem to have become intertwined with preexisting mythology from ancient Celtic and Welsh sources. For instance, in the second century, when Rome still ruled Britain, Roman forces defeated 5,500 Sarmatian warriors in battle. Rather than killing them, the Romans recruited these soldiers, and sent them to Britain to serve as border guards to defend against barbaric tribes of Scottish Picts to the north. These Sarmatians brought with them a culture rich in mythology and folk tales. Some of these tales involved a group of warriors led by a hero named Batradz. Batradz pulled a sword from a stone, had a magic cup that performed miracles, and threw his magical sword into a lake as he lay dying. Some historians have suggested that tales of Batradz appear to have found their way into the legends of King Arthur.

There also exists a wide body of ancient Celtic and Welsh tales of heroes with superhuman powers, who went on fantastic quests to rescue their women, or to seek out magical treasures. Many of these tales are very similar to tales which now exist about King Arthur and his knights, and it appears that over time, these tales became incorporated into the legends of King Arthur.